This article appeared as "Global Vision" in the Fall 2022 issue of Independent School.

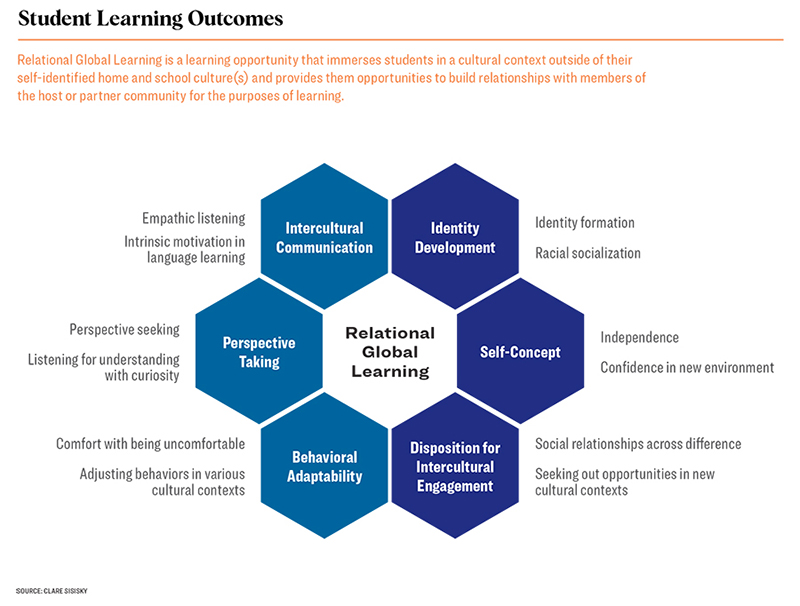

Over the past 10 years, many independent and international schools in North America have initiated or renewed efforts to engage their students across differences and support skill development in things like civil discourse, cultural agility, and understanding multiple perspectives, often using global competence frameworks from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Asia Society as a guide. Schools have also looked specifically to the analysis from OECD’s first Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) of global competence in 15-year-olds, which identified key areas that can lead to student global competence development: providing students with opportunities to relate to people from other cultures, in-person and/or virtually, was specifically outlined as one of five ways that schools can successfully prepare young people to be engaged global citizens and thrive in their futures.

Yet as schools have been designing and implementing immersive intercultural learning experiences abroad—such as experiential programs, immersive learning weeks, or similar initiatives—most have not assessed the long-term impact of these programs on their students or determined if the program curriculum and design are an effective way to develop the school’s learning goals. With this in mind, I designed a study to try to better understand the impact over time of short-term, school-organized international travel programs or exchanges.

Over the course of four months, I surveyed a total of 191 young alumni—former students five to eight years post-graduation who engaged in these international learning experiences during high school—from six different NAIS schools in North America that are also part of the Global Education Benchmark Group. I asked them to report if and how the experience influenced them over time, specifically whether they developed any of the global competencies of intercultural communication skills, perspective taking, and adaptability. The study, which collected both quantitative and qualitative data about the intercultural skills students developed, revealed several insights about centering the skills acquired and better designing global learning experiences and initiatives.

Listening to Others

Students in the study demonstrated significant skill in intercultural communication, or the ability to effectively communicate across cultures. A large majority (about 72% of participants) reported that their global learning experience in high school helped them learn this skill. This impact has continued into their young adult lives with 88.4% of participants saying their high school global learning experience has informed their current ability to modify the way they communicate with people from cultural backgrounds different from their own. A key area of intercultural communication that participants developed through their high school experience was listening with a real desire to understand the perspective and feelings of others.

Similarly, 77% of participants reported that their high school global learning experience helped them learn how to better recognize that people from different cultural backgrounds/identities may see things differently from them. One young alumna shared that her high school learning experience led to an ongoing desire to seek out multiple perspectives: “I want to challenge myself to see from every worldview, even if it’s a view that I don’t align with. I still want to know your view, I want to understand it, I want to know why you think that way, and I want to be uncomfortable. I want to be comfortable with my uncomfortableness.”

Adapting to Situations

We have seen over the past few years that students (and adults) struggled with the significant demands of adapting to the ambiguous and rapidly changing circumstances dictated by the COVID-19 global pandemic. But behavioral adaptability is a skill that can be taught and practiced, and 87% of study participants reported that their global learning experience in high school taught them how to adapt to different situations, especially when they were a guest in a culture that highly values hospitality. They also described how their skill and comfort with adapting to new situations led them to continue to engage interculturally, both locally and internationally.

The study also found that a structured and supported global learning experience in high school usually leads to a strong disposition for continued intercultural learning. Many young alumni described their learning experiences as a first step in a chain of decisions or thinking that led them to intentionally engage more across differences and feel more prepared to be successful in doing so after graduation. This was especially true for participants of color in this study, who were statistically more likely to engage interculturally than their white peers despite being underrepresented in higher education intercultural programs in the United States. This kind of learning experience positioned independent school alumni to seek out the numerous opportunities available to them in college and beyond.

Timing Matters

Young alumni consistently shared the importance of this experience having taken place during their adolescence. One young alumnus explained that the “time of my life that it happened … shift[ed] my perspective, not only on the world but also on myself. … It was the literal genesis to start building my identity, in my mind. … So, it’s shaped literally everything.”

Many alumni described their self-concept and identity as still in formation during that time in their lives, an idea supported by the literature and research related to adolescent neuroplasticity, which emphasizes that adolescence is a peak time when outside experiences influence cognitive brain development. This makes a clear case for the value of these learning opportunities taking place in high school, or even middle school, and for why an immersive program less than four weeks can still have a lasting impact.

Questioning Impact

Although these global experiences have many clear benefits, the research also found that some types of existing programming have limitations and should be rethought. Young alumni who participated in service-based programs—ones that primarily focused on conducting a service project such as construction or volunteering in a school or clinic—described a significant shift over time in their understanding of the value of these programs. Many expressed emotions of guilt and confusion, often instigated by college courses, readings, relationships, or intercultural engagement. Some had come to see such programs as problematic or as perpetuating what one young alumnus described as a “white savior complex.” They described how they began to question the service aspects of their experiences, sharing details about how they shifted their views over time and now see the service as reinforcing problematic power dynamics, involving what they saw as misguided explanations of who is helping whom, and perpetuating what they described as neocolonial mindsets.

The possibility of thoughtful and sustained community learning partnerships that are co-created and mutually beneficial, however, does exist. Reciprocal relationships with community-based organizations that help support student learning and community objectives are very difficult to execute at the high school level given limited resources (including time) to build and sustain partnerships as well as for critical student self-reflection before, during, and after travel. Schools and educators could benefit from a reflective review of Fair-Trade Learning principles, based on the work of Haverford College professor Eric Hartman, and how they might guide any continued or reimagined endeavors into community-based learning partnerships abroad.

Similarly, short-term high school programs had less of an impact on young alumni who identified as transnational (a person with strong identity-related ties to more than one nation). They shared how their identity had already provided them with opportunities to engage in intercultural contexts and to develop global competencies. For example, when asked about adaptability, one study participant shared that “when I’m at home I only speak Spanish, and I very much have a Mexican personality side of me that I can only be when I’m home; [when I’m at school] I have to adapt to be the American side of me.” Attending a predominantly white school—which greatly differed from her Mexican American home culture—provided this former student with ample opportunity to practice advanced intercultural skills. These participants also reflected on how their prior skill development was unrecognized by their school and not accounted for in the design of the program.

While assessing and differentiating for students’ prior knowledge and skill development may be common model practice in core academic classroom instruction or in athletics, it is not a common model practice for school-designed immersive learning programs, locally or internationally. Emphasizing social interaction and dialogue can support an opportunity for relational learning and organic differentiation so that all students can experience growth. This process meets a student where they are in terms of knowledge and intercultural and language skills and engages them in further learning.

Key Takeaways

To strengthen learning opportunities that can help all students effectively develop global competencies and intercultural skills, schools should:

- Prioritize relational learning as an intentional driver of intercultural program design, especially if the goal is global competence development.

- Highlight listening with empathy as a key way to develop student intercultural communication skills.

- Foster curiosity through first-person perspective sharing and dialogue, including with peers from different cultural backgrounds, to develop student perspective taking.

- Identify students’ prior intercultural skills and differentiate learning experiences to provide growth opportunities for all students.

- Evaluate or even reconsider international programs with a service focus and prioritize relational learning globally and community partnerships locally.

Read More

Check out the author's dissertation here.