This article appeared as "Brain Trust" in the Summer 2024 issue of Independent School.

In 2021, Kalyan Balaven took the helm at Dunn School (CA), and like many new heads of school, he knew he was about to face the many tests of leadership, including polarization and internal challenges. That’s why early in his tenure he tapped Kate Sheppard, principal consultant at SEE Change and someone he’d worked with before, to facilitate workshops about brain science research—how neuroscience impacts the way we collaborate, build relationships, and learn from each other. Balaven hoped that with this knowledge, his leadership team would be better prepared to navigate change and reach its full potential. In this edited conversation, Balaven and Sheppard discuss what their work has meant for Dunn School and how it could help other independent school leadership teams.

Kalyan Balaven: When new challenges come up, I’m more adept at responding to them because of the training and the work we’ve done together. The workshops, specifically around the amygdala [a major processing center in the brain for emotions], helped me understand how fear could be a motivating factor for some people facing a challenge. Knowing what flight, fight, freeze, and flock look like in a school community has helped me navigate through significant storms. The variable of fear is often unaccounted for in schools, yet it’s crucial to understand if you want to make strategic decisions that fit into the culture.

It’s been a few years since we started doing this work together, so I know the research has evolved. What am I missing today?

Kate Sheppard: That’s the million-dollar question. But I do have a sense that schools might be missing some of the big questions. The pandemic, the racial reckoning, societal unrest, war—all these things happening in our world—are shifting and shaping us and, as a result, our schools. A lot of schools are focusing on managing crisis while dealing with day-to-day operations. Those things are natural defaults, but schools need to use a neuroscience lens to understand how leadership and organizational development have evolved because we’re not going back.

Balaven: I think your work fills a gap. I find that educators are prepared academically to speak to the mind, whether you’re a sage on the stage or you use experiential modalities or different types of pedagogy. Then along the way, we decided that we need to do a lot more heart work—more empathy and equity and inclusion work. But this amygdala work around the fear variable, and how people view their work, is a level of thinking that can move a community through crisis.

After the October 7th Hamas terrorist attacks on Israel, a lot of heads of school were trying to workshop community statements. I was more interested in putting together a yearlong seminar with invited speakers from academia, the Anti-Defamation League, and those with lived experiences in the region and across the spectrum. I was also thinking about important school field trips to the Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles and the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C., so our students could fully understand the complexity surrounding such violence and its context and impact and could begin to process these perspectives in a way that factored in the fear they were all feeling. Some of my peers went into statement mode because they feel like a statement speaks to the mind and addresses the heart, and then we can move on. But we can’t move on because the subcommunities in our schools—whether educators or students—are having their own fear response, and they cannot process it. You have to go through a very slow and strategic build to help them do that.

Sheppard: Everything we do to educate young people will be overridden if fear is present and if we’re not adaptive. I don’t bring my best self as an educator if I am afraid. Fear is permeating society in such intense ways. Anxieties are up from the pandemic still, and there are domino effects from that. Like you, I’ve heard heads of school saying that when something happens in the world, they immediately start texting other heads of school, “What language are we using? What word are we using? Am I using the right or wrong word?” I think that is indicative of fear. These fears don’t have to be rational at all, but they’re driving so many of our behaviors—whether or not we recognize it, because 95% of our behaviors are driven subconsciously.

Balaven: Having attended your workshops over the years, I incorporate things I’ve learned, like brain types, when I’m interacting with a colleague or student. I can be like, “OK, I know what your brain type is. And I know that your perspective comes from the fear response in your life, whatever it is.”

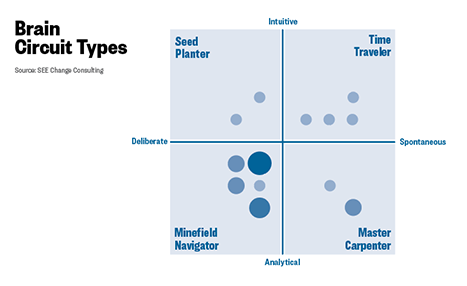

Sheppard: Right, we’ve talked about the Brain Circuit Types, an assessment process that attempts to identify neuro-cognitive loops in the higher-functioning part of our brains that drive motivation, work style, communication, time horizon, and so much more. Individuals are mapped across quadrants, with those closer to center being able to adapt to other styles more easily and those further from center specializing in their approach. We can use this tool to better understand how to leverage their strengths, manage their liabilities, and create more inclusive spaces. (See chart above.)

Think about how much of our time and energy right now is going into unproductive conflicts. Those conflicts are indicative of our fear-based brain and reluctance to engage with empathy and curiosity.

Balaven: In every single issue I’ve dealt with in my career and education—whether complex, like the pandemic or the racial reckoning, or something more microcosmic, like a microaggression or challenges with a colleague—I now realize that everyone’s fear response was playing itself out. Now when I have a conflict, I wonder what was triggering the other person’s fear response that they dealt with me in that way. That helps me reframe my mindset to focus on resolving the situation.

Sheppard: First of all, I love that example of how you were able to optimize the understanding of brain types. When we present brain types to schools, one thing that sometimes comes up is, “If I’m mapped in this particular quadrant, if I’m a Minefield Navigator, for example, or I’m a Time Traveler, is my goal to move to other quadrants? Am I supposed to be closer to the center of the axes?” And my answer is always no. Our goal is to understand ourselves better so we can leverage our strengths, manage our liabilities, and create more space for other people’s work.

Balaven: I find in meetings, and in moments with people in those different quadrants, I’m trying to understand the way in which they’re seeing things. I’ve found that parroting or reflection helps bring down their own fears so I can then share another perspective.

Sheppard: It’s almost counterintuitive that the more we understand about each other personally, the more it depersonalizes stuff. You can understand that something is playing out the way it is because of that fear response. It can help you realize, for example, the reaction has very little to do with you, even if you were the catalyst for it. And if you can engage with that curiously to understand where that person is coming from, knowing that it’s based on something that happened to them, then you have a more productive way of engaging with them.

Balaven: When I brought you out to Dunn, it was important for my transition into the school. I didn’t really have a transition time with the previous head, and the school was in crisis in some ways. But through our work, I was able to organize a team effectively. We were able to optimize everybody and see each other. How do you scale that to all of our schools?

Sheppard: That perspective-taking is how we learn from each other. It opens up our thinking. This is why I think there is so much value in understanding some of the idiosyncrasies of our brains. Disequilibrium, discomfort, and fear can cause cognitive distortions known as projections and polarizations. Projections are the “you should do it the way I would/you should have anticipated my needs.” Polarizations are “I’m right, you are wrong/I’m good, you are bad.” Projections and polarizations can do real harm to individuals and communities. We don’t create space for other people’s perspectives; we just battle to protect our own. But holding a paradox is the antidote to this.

Schools are existing among paradoxes. For example, they’re inclusive and exclusive by design. Leaders exist in paradoxes—it’s their job to fix it and not fix it. Teachers live in paradoxes, as author and educator Parker Palmer reminds us, holding a space for the voice of the individual and the voice of the group. We are focused on caring for others, and we are focused on ourselves. We are selfless and selfish. We care and we don’t care.

Accepting these paradoxes can be difficult, but they are also humanizing. Schools need paradox more than ever, as others project on them to solve unsolvable issues. Increasing awareness around these things, from a very basic workshop level to a deep dive, can really be beneficial.

Balaven: I’d love to see this work beyond schools. In this country, rather than entering into discourse, we enter into this polarization where we are so far away from each other. We need to live in the paradox.

Sheppard: Fundamentally there are paradoxes we will choose not to hold, that we can’t hold. But when we can hold it, we are open to more possibility. When we can come together in dialogue, when we can practice holding a paradox, it can be healing for ourselves, for others, and for our community.