.jpg?width=300&height=200) A few weeks ago, I came upon a treasured memento: my son’s Pinewood Derby car, which he built himself when he was in second grade. If you are unfamiliar with the Derby, it’s an event where children build and decorate an unpowered car, generally from a kit, to race against other students, often in organized scout troops. When my son came home with the kit, I approached it the way my parents approached my school projects—I was there for questions and support, but the car was his to build and decorate. At first he protested that it was too hard and that he needed his parents’ help, but eventually he became completely engrossed in the project and finished it in time for the race. The resulting car was a bit ramshackle, but he was immensely proud of it, as his dad and I were of him. The day of the race, he ran into school to share his masterpiece, only to be ridiculed by some of his classmates, who boasted sleekly designed cars, clearly built by adults. He was hurt by their remarks but still proud of his car. Although it may not have been the most glamorous car on the track, it turned out to be very quick, and he came home with a second-place ribbon.

A few weeks ago, I came upon a treasured memento: my son’s Pinewood Derby car, which he built himself when he was in second grade. If you are unfamiliar with the Derby, it’s an event where children build and decorate an unpowered car, generally from a kit, to race against other students, often in organized scout troops. When my son came home with the kit, I approached it the way my parents approached my school projects—I was there for questions and support, but the car was his to build and decorate. At first he protested that it was too hard and that he needed his parents’ help, but eventually he became completely engrossed in the project and finished it in time for the race. The resulting car was a bit ramshackle, but he was immensely proud of it, as his dad and I were of him. The day of the race, he ran into school to share his masterpiece, only to be ridiculed by some of his classmates, who boasted sleekly designed cars, clearly built by adults. He was hurt by their remarks but still proud of his car. Although it may not have been the most glamorous car on the track, it turned out to be very quick, and he came home with a second-place ribbon.My first reaction to this situation was to question my parenting—should I have helped him more? Only one other parent had not designed their child’s car; were we the bad parents in the group? In retrospect, I also should have considered whether my anxiety over my perceived failure was impacting his reaction to the situation.

The Parent-Child Anxiety Cycle

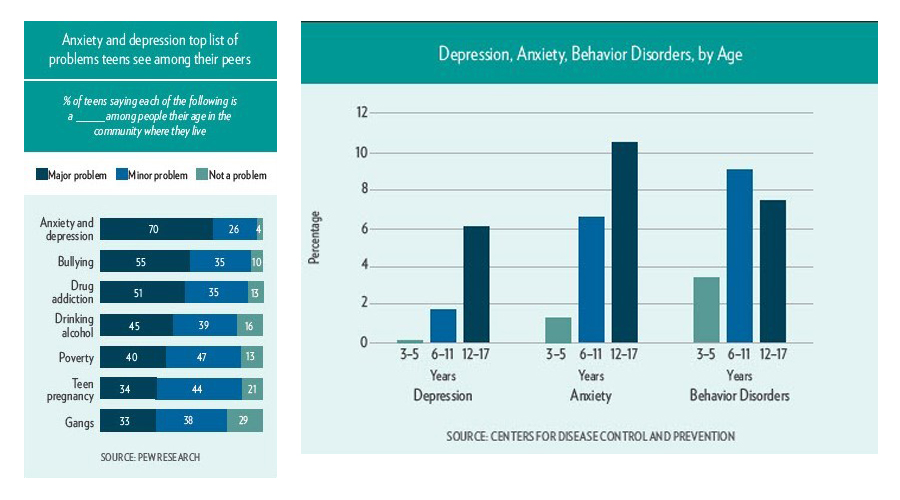

For every parent, there comes a moment when it’s time to let your children venture out on their own, even if you know they may get hurt or fail. We know that failing and getting back up is essential to a child’s development, but it’s always hard to see those tears, watch the frustration, or observe the anxious moments. It’s even harder today when there is so much over-parenting. You question whether you’re doing too much or too little as a parent. When I visit with parent groups at schools, I see this second-guessing often. Parents make what they think are the best decisions for their children but as soon as something does not go as planned and their child gets upset or fails, they second-guess their choices and anxiety creeps in. Experts say that this can be the beginning of a vicious cycle in which parents react to a child’s perceived anxiety, which results in a cycle of the parent and child feeding each other’s anxieties. Social media only intensifies the problem, as students and parents alike are bombarded by messages about the need for perfection.In a recent Pew Research study, teens today identify anxiety and depression at the top of the list of problems among their peers (see chart below). The numbers are astonishing—70 percent see anxiety and depression as a major problem. The Pew study goes on to identify the drivers of anxiety: 35 percent of girls and 23 percent of boys feel pressured to look good, while 36 percent of girls and 23 percent of boys feel nervous about their day in general. Nearly all teens feel some pressure to get good grades (90 percent), with more than 60 percent noting that they feel heavy pressure to get good grades.

Interestingly enough, although parents may drive some of this anxiety to achieve, they, too, are aware of and concerned about the problem. In a 2015 Pew Research study, 54 percent of parents responded that they were worried that their children might struggle with anxiety or depression. The study also found that parents worry about their parenting skills, with 46 percent saying that their children’s successes or failures were tied to their parenting skills as opposed to the child’s own strengths and weaknesses.

Rising Rates

How does all of this play out? According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 7.1 percent of children ages 3 to 17 years (approximately 4.4 million) have diagnosed anxiety, while 3.2 percent of children ages 3 to 17 years (approximately 1.9 million) have diagnosed depression. These conditions increase with age (see chart above).Suicide rates are also going in the wrong direction. Although they had been dropping in the ’80s and ’90s, suicide is now on the rise for all ages. The most alarming trend is the rise in suicide by young girls. Although girls between the ages of 10 and 14 make up a very small portion of total suicides, the rate in that group tripled over 15 years from 0.5 to 1.7 per 100,000 people, according to Sally C. Curtin of the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics. One theory researchers are studying is that girls are reaching puberty earlier and, because of that, girls are facing anxiety, depression, and other psychiatric disorders earlier in life, when they are less well-equipped to deal with them.

Curbing Destructive Cycles of Anxiety

Parents, teachers, and school leaders all have a role to play in keeping children healthy. Ironically, many of the steps parents take because they think they will put their children on the path to success may actually stop them from becoming leaders and instead make them anxious and afraid. In a 2014 forbes.com interview, Tim Elmore, leadership expert and founder and CEO of Growing Leaders, calls out seven parental behaviors that are keeping children from becoming the leaders they are destined to be:- We don’t let our children experience risk.

- We rescue too quickly.

- We rave too easily.

- We let guilt get in the way of leading well.

- We don’t share our past mistakes.

- We mistake intelligence, giftedness, and influence for maturity.

- We don’t practice what we preach.

In her new book, Under Pressure: Confronting the Epidemic of Stress and Anxiety in Girls, Lisa Damour, psychologist, author, and executive director of Laurel School’s Center for Research on Girls, provides some useful strategies to rethink the anxiety cycle. She opens the book with a quote from Anna Freud, which, although written in 1965, nicely frames the challenges we face today:

It is not the presence or absence, the quality, or even the quantity of anxiety which allows predictions as to future mental health or illness; what is significant in this respect is only the ability to deal with anxiety. The children whose outlook for mental health is better are those who cope with the same danger situations actively by way of resources such as intellectual understanding, logical reasoning, changing of external circumstances … by mastery instead of retreat.

Damour takes the approach that stress and anxiety must be addressed head-on and describes that “stress rises when our daughters are pushed to operate at the edge of their capacities.” As teachers know, there is a yin and a yang to this—stress has a positive side and helps us all to grow and develop, but when it exceeds our emotional and intellectual capacity to deal with it, stress moves into negative territory. Damour points out that the solution to keeping that stress and anxiety on the positive side lies in helping girls—all students, really—in knowing how to restore themselves.

In his book, At What Cost?: Defending Adolescent Development in Fiercely Competitive Schools, clinical psychologist David L. Gleason suggests that we also need to re-examine our trend of hyperschooling, that is “overworking, overscheduling, and overwhelming” students. He suggests that we need to understand what the developing brain can handle and adjust accordingly.

Both books offer great strategies for parents, teachers, and leaders. We can break the destructive cycles of stress and anxiety while helping children, in Damour’s words, “recognize that being stretched beyond familiar limits cultivates strength and durability.” We also need to take time to bring parents into the conversation so that they can be partners in breaking unhealthy practices. I would suggest that this is our most important work.